First moment: I’m talking to my girlfriend. In seven years, we’ll both be married to other people and living on separate coasts.

It’s one of those lightly fraught conversations that’s constantly teetering on the edge of an argument. That’s our dynamic. I have no idea why we’re talking about estate taxes, but we are. My understanding of them is highly unrefined, whereas hers is not, but I do not want to admit this.

“My belief is that if you are an extremely wealthy person, you shouldn’t be able to give that wealth to your children after you’re dead, beyond a small amount” she says. I don’t particularly disagree on this point, but our entire relationship is built on constant, low-level intellectual brinksmanship, so I do what I’m destined to do and comment anyway. “What if the kid’s severely disabled or something? Aren’t they entitled to that money to pay for care?” I say.

She looks me dead in the eyes and says “those people should be provided for by the state.” And I don’t have an answer for that. And I’m uncomfortable because I can sure enough feel the rasping, groaning sensation of the ethical functions in my brain now attempting to process a very big, very complicated idea that I am certain is a Correct Thing but have managed to never think about very much. She rightly clocks that I don’t have an answer, so the conversation moves on and eventually I stop answering her texts.

Second moment: I’m sitting in a sociology class, several years earlier. The professor poses a definition of how mental illness is interpreted and perceived by those who don’t identify has having it. “Simply, it’s the persistent violation of social norms.”

He continues. “Here’s an example. Say you were to go home to your dorm, and take a seat on the couch, and just stare directly at the wall silently for hours. Your roommates might call you mentally ill for that. You’re not being violent or erratic or delusional. You’re just doing something that’s not right.”

Though Frederick Wiseman’s not the first person to change careers and pick up a camera, the story of how he did, and what came after, is a deeply uncommon one. Simply put, he made a movie that royally pissed off the state of Massachusetts.

In broad strokes: In 1967, Wiseman was working as a law professor at Boston University. As part of his class curriculum he would bring students to visit Bridgewater State Hospital. Located an hour south of Boston, Bridgewater has been operating in some iteration or another as a state-run dumping ground for society’s undesirables since the mid-19th century, when it was opened as an almshouse. It’s currently billed on the Mass.gov page as a “medium security facility housing male patients in several categories: civil commitments without criminal sentences, and on occasion, pre-trial detainees sent for competency and criminal responsibility evaluations by the court.” And in 1967, it was where you would encounter men officially defined as “criminally insane” and locked away because of it.

The story behind what Wiseman saw in Bridgewater State Hospital, and how he was able to show us, is a story of cruelty bound up in incompetence. A variety of people had to fuck up to let this movie happen. Wiseman never could have secured permission to film without benefiting from the same institutional incompetence and neglect that visited so much harm on the men it was meant to rehabilitate. Anyone with even a child’s sense of optics would have realized how the goings-on at Bridgewater would look to an outsider, but Wiseman still somehow received the go-ahead to stick around for a month and amass hours of film.

It’s possible that Wiseman, absent being associated with a media outlet or a regulatory body, didn’t give off the unease-inducing energy of a journalist or an overseer. Maybe the workers and administrators of Bridgewater lacked any shame whatsoever. Maybe they felt like they were beyond questioning because they housed and fed these people, and couldn’t possibly imagine a viewer sympathizing with the inmates more than the overseers. Maybe he just was the kind of guy who, even with a camera and mic, was really easy to forget was in the room.

In any case, Wiseman’s finished product was damning, depicting all manner of emotional and physical abuse of inmates short of actual beatings. It was such a bad look that the state of MA actually sued Wiseman to squash its release, which is traditionally very hard to do thanks to the First Amendment. They almost won, too. Their argument was that Wiseman was violating the inmates’ privacy, which must have been a hilarious argument for Wiseman to hear given that it was coming from the people who often refused to give their charges clothes or treat them with even the basic elements of respect.

Wiseman fought the state to a draw, and the court ruled that screenings of the film could only be allowed for medical or social scientific purposes. But since the Streisand Effect is real, this gave Titicut Follies instant cult status. Decades later, it was finally afforded wide release because most of its subjects were dead. It’s been canonized as a fearless and groundbreaking work that helped drive a broad, ongoing cultural reckoning with how mentally ill people are controlled by the state, hidden away, and inevitably abused in absence of sufficient oversight.

I have easily seen things far more upsetting than Titicut Follies, though that’s not something of which I’m particularly proud. My first personal internet connection gave me instant access to any hideous thing I might be curious about, and in chasing the edgelord voyeurism of youth I quickly built up a taxonomy of shocking moments or sequences I had or could view on film. I’m a listmaker by nature, and I sat through a lot of very boring, very violent foreign films out of a need to explore exactly how fucked up the movies could get. I’m by no means some jaded wreck, because I managed to learn something quite useful - namely, that it’s okay and often very good and healthy to see something and feel upset, even if that makes you impulsively want to turn away.

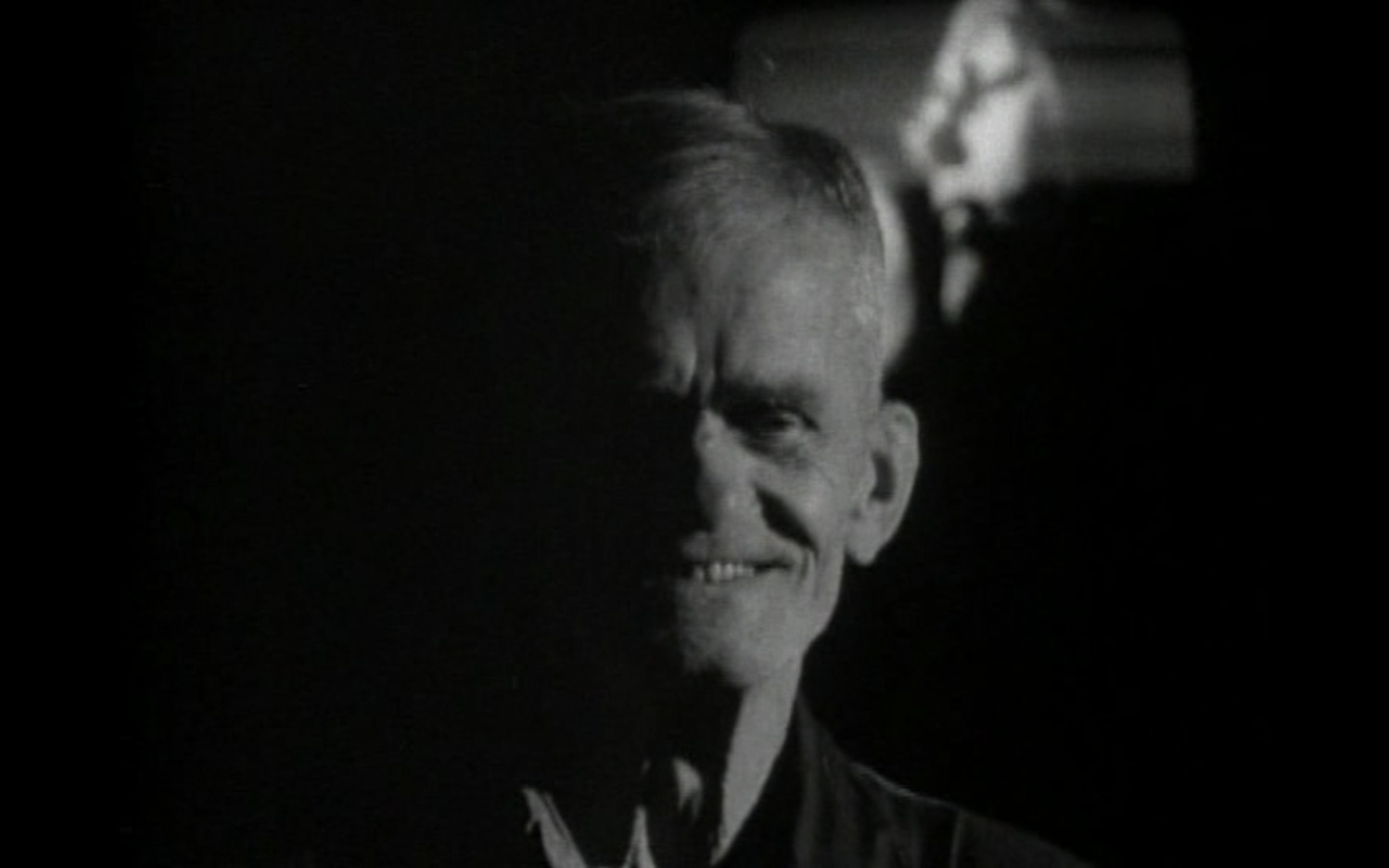

Malinowski is an older inmate who lives, if you can call it that, in solitary. The cruel totality of his isolation has broken him. He can speak, but barely. He’s often naked. The guards taunt him constantly and refuse to give him clothes. After he refuses to eat, they strap him down and force-feed him through a rubber tube that gets threaded into his nose and down his gullet by a pitiless doctor. Malinowski closes his eyes and tears up. The doctor almost ashes his cigarette into the elevated funnel that holds Malinowski’s nonconsensual lunch.

Then, the scene cuts, and the sound ebbs. Suddenly we’re looking at a still, rigid face. His tightly shut eyelids look oddly flat.

Then, jarred, it’s back to the force-feeding. Back to the man’s face. One more of these switches and I realize that this man is Malinowski again, but he’s dead now and being prepared for burial.

This is likely the film’s most infamous scene, and I was prepared for that going in. But it wasn’t what I expected. The whole scene is very businesslike, even the cuts to Malinowski’s corpse. The doctors and orderlies keep up a steady patter and if you were to close your eyes you might think you were hearing the thrum and bustle of any doctor’s office. They even throw encouragement Malinowski’s way, and when he’s done and the tube is removed, he even cracks a joke on his way back to his cell.

The power of Wiseman’s style is that this scene doesn’t have to be outwardly violent in order to projects its cruelty. It doesn’t need to be a simple pitch of evil against innocence, with Adagio For Strings blaring in the background, in order to devastate you. It’s only in retrospect that you realize Malinowski is so docile because this is one of many times he’s suffered this treatment. Wiseman’s camera just happens to catch this one.

***

The orderlies and workers do their jobs. One nurse with a voice like Jerri Blank reads a note sent to her from a former inmate, who has since been transferred elsewhere, or possibly released. She seems pleased to have heard from him. Her fellow nurses chime in: ““Well you at least ya tried”. “I hope we cured him!”. Big grins all around.

Bridgewater is filled with people, all of whom get moved around like so much inventory, through blood and shit and sweat and so much fucking cigarette smoke, and basic humanity is rarely an option. There are moments so odd and contextless that bubble up through the film’s narrative and rise to the level of absurd - a political debate ripe with revolutionary fervor breaks out between a young and an old inmate, a man on the yard plays tuneless trombone music to no audience, a pedophile gets grilled by his doctor over how pretty his wife is and how that may have caused his crimes. We have no way to know how these men arrived, or why, or when. They all just keep wandering, or being led, through the frame. There’s a regular unsettling experience when an inmate or a worker will catch the camera’s eye and you’ll almost want to shout: Hey! Hey! I see you! But they never keep eye contact with us, probably because the middle distance is a far more calming sight, whereas Wiseman and his crew’s presence is a reminder of the outside.

Vladimir is sharply aware of what’s happening to him as an inmate. He implores with the doctor in the yard to let him go, that it’s wrong to have put him here. “If you leave me here, that means that you want me to get harmed. That’s absolute fact. That’s plain logic. That proves that I am sane.” The doctor chuckles, lights a cigarette, staring out through boxy shades. “That’s interesting logic.” Later, a panel of doctors agree that Vladimir requires a more aggressive form of treatment to curb his paranoia. Their faces fill the frame. The smoke curls past their ears, and their meeting is adjourned.

It’s nearly impossible to sympathize with the doctors and orderlies, yet the film isn’t about the evil of individuals. As Wiseman discovers, the greater story is in the system that compensates them. Footage of the hospital talent show (from which the film draws its name) bookends the movie, and in it, the mood is transformed. Everyone is smiling and nobody is haunted. Employees applaud inmates, instead of insulting them. My guess is that the talent show acted as a pressure valve so that the ongoing slow horror in which all are victim or complicit doesn’t feel quite as overwhelming. A little breathing room gets to b crucial when you live in a smoke-filled room.

In his 1968 decision to partially ban the film, MA judge Harry Kalus wrote that Titicut Follies is: “crudities, nudities, and obscenities. 80 minutes of brutal sordidness and human degradation. A hodgepodge of sequences, the camera jumping helter-skelter. There is no narrative, each viewer is left to his own devices as to just what is being portrayed.” Therefore, “No rhetoric of free speech and the right of the public to know can obscure this [picture] for what it is: trafficking in human misery, degradation and sordidness of the lives of these unfortunate humans.”

I am far better versed in the discourse of disability rights than I used to be. I am far more aware of the social and legal choices that tossed mental illness, criminality, torture and neglect into hidden spaces free of oversight where people would be hurt and killed with zero consequences, partially because Wiseman brought viewers into those spaces. So what happened after that? Imagine deciding to make a movie. Then, in doing so, you capture something so dangerous that an entire state’s resources are mobilized to bring you to heel. Imagine fighting that as hard as you possibly can, and imagine then what you would do once that’s done.

What Wiseman did is keep going. He turned his camera back on and let it run for fifty years. If my first project was received like that, I might do the same out of sheer spite. But I am afraid of what I might see in those fifty years, given where he started. Not every one of his movies will be this brutal. But the truth is harsh and disturbing, and there’s so MUCH of it in here.

I rode home on the F train and the automated announcement told me not to give to panhandlers, because it’s illegal and instead, it helpfully suggested to donate to a New York City shelter, because that way the money can be aggregated and channeled by someone somewhere who has a desk and a job title and is presumably working hard to turn your money into progress, and the recorded message is there to tell you it’s that person’s job to look at and deal with those people, not yours, so you should turn away and go on your phone and enter payment info into the donation portal and let those people shuffle past, let them go on living somewhere else, and look away, because that’s okay.

Coming up next: I watch Wiseman’s 1968 film High School, which features a day in the life of Northeast High School in Philadelphia.

P.S. As some of you might have heard, Kanopy (aka the place where you and I can stream all of these movies) is no longer going to offer free access via the NYC library system starting next month. Here’s why. But don’t worry - this newsletter absolutely will continue as planned. In the meantime, Kanopy users can still see Titicut Follies here.

P.P.S. If you enjoyed this newsletter, feel free to forward it!